“Why did you become a Hindu?” Sometimes the question arises. Most often it is unspoken and merely expressed in the form of raised eyebrows as someone processing a document reads what I’ve filled in under “religion”. And requires no answer. But occasionally a customer in my little shop may begin proselytizing when I mention my marriage to an Indian man and the twenty years I lived in India.

And then I leap to defend my Hindu faith.

“But why did you convert?” is the inevitable question after a few moments of silence. The eyebrows rise even further and often lips tighten in disapproval as well.

Then I tell them the story of Beejee’s Mandir. It’s a true story. But it’s not the whole story. My pathway into a philosophy so different from my family’s faith was definitely a much more complex evolution over the years than a single incident could engender. But I offer the story of my mother-in-law’s mandir as an explanation because it is so replete with love, tolerance and respect for another culture and religion that I’m sure the Universe smiles whenever I share it.

The truth however, is that my reasons for straying away from my Protestant childhood began very early in my life and have become blurred a bit. When I was about thirteen, the concept of reincarnation catapulted into my life in the form of a book entitled simply “Reincarnation” which my mother borrowed from the library and left on the coffee table. I thumbed through it, fascinated not only by the roster of eminent people who espoused the idea of multiple lives but by something resonating deep inside myself.

A feeling of something unanswered being “answered”. Reincarnation. Of course. I’d lived before. The vague feelings, the odd moments of recognition and the abilities I seemed to have brought with me from somewhere as a very small child. Some things I never had to learn. I somehow knew them. Reincarnation was my answer. I was just remembering things I’d known before.

Now I understood why I cried when I first heard Mozart, I was only three or four and all I could do was hold my hand over my chest and wail. My parents had no interest in classical music. But Ezio Pinza singing Mozart on Uncle Bill’s old Victrola reduced me to what can only be described as pure emotion. I knew that music, I remembered it.

And the drawings were even more peculiar. A teacher holding Saturday coloring classes for toddlers stammered as she told my mother that no child my age could possibly understand perspective and anatomy. And that she believed her eyes only because she’d seen my hands wobbling over the paper and producing what ordinarily should not have been possible. I hated the classes because as I told my mother ” It’s all bad … everyone colors things bad … their people shapes are bad. ” The children’s scribbles were so obviously crude that they made me angry.

I was often angry and threw horrendous tantrums. My mother was reduced on several occasions to pouring a glass of cold water over my head to startle me out of my rages. Only years later she and I both began to put the pieces together. I had been frustrated. Frustrated when my hands wouldn’t cooperate with my pencil, when a piece of plasticine resisted my attempts to form a sleeping cat or a flower petal. My brain knew what it wanted, but my fingers wouldn’t oblige.

I was trapped in this woefully inept body and in my struggles to get it up and running properly, I was repeatedly thwarted by being a child in a brand new body. Simple. As I grew up and my body began to obey the commands of my brain, the tantrums vanished. And I reveled in what was obviously a good head start. My talents were only memories. If I closed my eyes and let myself relax, then the drawings would just flow.

In the ensuing years, I don’t remember discussing reincarnation with anyone other than my mother who became more and more convinced that it was indeed true. She even insisted that the Bible made oblique references to reincarnation and the Essenes. And that it in no way conflicted with her version of Christianity. My father remained outside this dialogue. He eschewed church, discussions on religion or politics and any topic which might lead to dissension. He wanted peace and quiet in the home.

So several years later, when I came home from New York for the Christmas holidays and announced I was going to marry a graduate student from India, I got two very disparate reactions from my parents. After a few moments to gather herself together, my mother murmured somewhat weakly, ” Well at least he’s not Catholic.” In those days in Quebec, the animosity between Catholics and Protestants was muted but strong enough to keep both denominations socially isolated from each other.

My father on the other hand was more voluble on the matter. “It’s your fault, Maxine, ” he stormed. “You put all those wild ideas about reincarnation in her head when she was a child,” he said, stretching the time line a bit. And he left me no doubt as to where he stood on the subject. I was making the worst mistake of my young life. Worse than choosing music and going to New York to study at Juilliard instead of opting for linguistics at McGill and staying safely at home in Montreal.

Worse than dying my hair black and wearing pant suits and insisting that Charlotte Whitton should be Prime Minister of Canada. Or writing anonymous letters to the Montreal Star as ” Najan Toreski.”. Oh this marriage was the worst decision I would ever make. And I planned to follow my husband back to India where his family owned several businesses. A business family in Bombay! That was just too much for my parents to tolerate. They were definitely biased in favor of academia over business.

Even though both Mom and Dad calmed down enough to promise no more would be said during the Christmas holidays and that I should think very carefully, it was an uncomfortable week before I flew back to New York for my last semester. And vowed there would be no more visits home until I left for Bombay.

*****

In the year which followed, both my husband-to-be and I graduated. He went back to India to prepare his family for his “American” bride. As far as they were concerned Canada was simply an outpost of the United States and no leeway would be given for my birth country’s link to England. It was the same to them. I was a “Westerner” and I was not welcome.

And my own family was equally intransigent. So I remained in New York where I found a job with Oxford Press and was assigned to some very odd editorial assignments involving arcane publications which required advertising blurbs. The most difficult of which was a book entitled “Enûma Eliš ” written entirely in Babylonian cuneiform script. And the wealth of detail available on Wikipedia today wasn’t available to me then. The only fragment of English to be found was the publisher’s name on the back cover. Oxford Press.

This particular assignment filled me with foreboding. Hindi was a script too and although absolutely phonetic, the characters weren’t remotely similar to anything I’d ever seen. Babylonian cuneiform and the Hindi Devanāgarī looked equally daunting.

I sat there in the Oxford library, desperately trying to cobble together two hundred words designed to entice a prospective buyer into purchasing this book which clearly would attract a very limited readership no matter what I wrote. And fretting over the possibility that all the books in India would be printed in a similarly indecipherable script. I was prepared for a diet heavily slanted towards spicy curries and a wardrobe which ensured I would be suitably covered from head to toe. But books and magazines? Not being able to read? That did worry me.

My trepidations were becoming more and more obvious to my co-workers, one of whom left a book for me on my desk one morning. A lovely leather-bound book describing the social and religious customs in India. I thumbed through it and was mildly worried by the “64 Indian Arts” which were apparently required of all new brides. I knew I was okay with needlework and music, but there were other arts I knew nothing at all about. Rice paste patterns on thresholds and traditional mendhi or henna designs for hands and forehead seemed possible to fake. But well over half of the skills were totally unfamiliar to me. I would have to learn fast.

I should have noticed Diane’s mischievous grin as I flipped through the pages. However it wasn’t until I reached the chapter on Sati that I realized something was wrong. I knew that in the past a Hindu widow was expected to fling herself on the burning funeral pyres of her deceased husband. But not nowadays! Sati had been outlawed for at least a century. I was puzzled for a few moments and then turned my attention to the inside cover page.

The book was a reprint by Oxford University Press. The original was first published in 1825.

*****

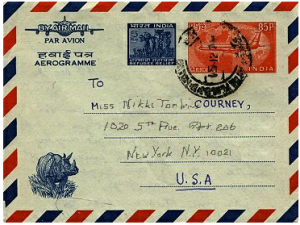

Somehow I survived my eight month’s employ at Oxford. Letters from my mother were confined to the details of her trips to gather fiddleheads from the woods and her latest weaving project. She judiciously avoided all mention of my upcoming marriage plans. But I was fortified by encouraging letters from Naresh which regularly arrived every three or four days and were covered with wonderfully odd-shaped and vividly colored stamps.

As we joked in our letters about my “dowry” I was slowly accumulating my trousseau, carefully packing dishes and small electrical appliances not available at that time in India. And American polyester fabrics which he assured me were the pinnacle of fashion in Bombay and would please my new bhabis or sisters-in-law.

Somehow I managed to arrange for shipping a refrigerator and all of my crockery and fabrics by March, after being warned it would take two months for the items to arrive in Bombay. Then I went back to Montreal for a final visit with my parents.

And a miracle had happened. Realizing that I wasn’t going to change my mind and sparing me the anguish of having to make a choice between the man I loved and my own family, my parents capitulated, My father sat in his chair gruffly looking at me from under his long silver eyebrows. ” So you’ve decided you’re definitely going to marry this man?”

I sat with my head down, tears nudging at the corners of my eyes and beginning their descent down my cheeks. I managed a feeble nod.

Father gave me a long silent look before his lips softened just a trace. He cleared this throat. ” Well I guess the Tomkins family has to be represented at your wedding. How would you like your mother to go to India for the wedding?”

Overwhelmed, I couldn’t speak for a moment and then managed to whisper, ” There’s nothing in the world, I would love better …”

Another throat clearing and a shuffle of his feet against the carpet. Then Dad murmured almost inaudibly, ” And how about it if I came along too?”

There was a moment of silence before we were all in each other’s arms, rocking back and forth, crying and taking turns swiping at each other’s tears.

*****

Two months later we were gathered together in the lovely gardens surrounding my in-law’s homes in Amritsar, the holy city of the Sikhs about three hundred miles from New Delhi. Over a thousand people had congregated to celebrate the marriage of Naresh Seth, scion of the powerful and prosperous Seth family to Nikki Tomkins, eldest daughter of the blue-blooded Tomkins. My mother-in-law, “Beejee” was unofficial master of ceremonies, breaking the tradition of widows taking the back seat for every function.

Both families at first had felt the other family had gotten the best of the bargain. Until they discovered these feelings were mirrored on both sides. When this occurred to the huge Seth family and the greatly outnumbered Tomkins, there was a dawning moment of mutual realization, followed by a great deal of laughter and back-slapping among the men. And the celebrations were duly expanded to fit the occasion of such a prestigious alliance.

The wedding went on for three days. The city of Amritsar blacked out twice, when the electrical grid broke down as more lights were added to the wedding decorations. And I learned days later that the news of the Seth-Tomkins wedding had swamped news of the Indo-Pak war, which was simmering on the border about twenty miles away.

When the festivities wound down and people began returning to their normal routines, it was time for my parents to leave for New Delhi to catch their flight back to Montreal. We stood on the train platform at the little Amritsar station. As my parents embraced their “Indian” bride-daughter, there were a lot of tears. Suddenly Beejee moved forward and gently added her arms around me as well, She murmured something in Punjabi and my sister-in-law translated, ” I will care for your daughter as if she is my own.”

As the train pulled out, Beejee’s dabbed at my tears and hugged me so strongly I could hardly draw a breath. My new family gathered around me in a huge circle and we all waved towards the train as it slowly pulled away from the station.

*****

After the wedding guests dispersed, my husband and I remained In Amritsar with Beejee and Naresh’s brother and wife, Pammi. We lingered on for a few more days in order to rest a bit before continuing on to Kashmir for our honeymoon. It gave me time to sit with Beejee and start to develop the mixture of hand signals combined with bits and pieces of English and Hindi which was to become our to become our own personal language. And to cement my friendship with Pammi-bhabi, who had quickly become my mentor and favorite sister-in-law.

After about a week we set off for Kashmir, the favored honeymoon destination for young lovers and a favorite venue for Bollywood romances.

We took a room in an old-fashioned hotel in the summer capital of Srinagar and began to explore all the popular landmarks. We strolled through the legendary Shalimar gardens with their lush rose beds and reclined on silk cushions in a traditional wooden shikara as the oarsman paddled through the lotus pads towards the middle of Dal Lake. We sampled rich Mughlai curries and bought several lovely embroidered shawls.

But finally it was time to go back to Bombay and begin setting up our household. The next few months were a flurry of activity as we moved into a new apartment and called in carpenters to make closets and a tolerably Western-style kitchen. Which meant pulling out the mori, a crudely tiled vegetable washing drain and installing a small stainless sink. A cook was found to make Naresh’s curries while I subsisted mainly on boiled eggs as my stomach slowly acclimatized to the water, the spices and the unfamiliar diet.

And our social life blossomed. The rounds of parties which had accompanied our wedding celebration in Amritsar seemed to have merely shifted venue and we were feted by an astonishing number of people. Now there were dinners and lunches and movies and birthdays and more weddings with even more dinners. The Seth family was huge and the most remote relationships were considered as close as blood siblings.

So it was nearly a year before I returned to Amritsar to visit Beejee. who spent half the year with Pammi-Bhabi and her husband in the beautiful home where I’d been married. The upstairs guest bedroom had been christened ” Nikki’s room” after my wedding night and remained so for all the years I lived in India.

Now I was visiting alone, ostensibly to gain a little weight since I’d been ill quite often in my first year in Bombay. The well water on the family property was rumored to be an excellent curative and Punjabi cuisine was known for its heartiness and liberal use of ghee, a clarified butter which packed five times as many calories as ordinary butter.

Pammi-bhabi had set her cook to work preparing large pots of ghee and was for the first time allowing meat and chicken to be cooked at home. She greeted me with this news at the train station moments after I arrived, so pleased with being able to offer me the ultimate hospitality.

“But Pammi-bhabi …. what about Beejee?” I began as we climbed into the car. I was worried at the thought of upsetting Beejee who had been so good to me. I knew Beejee was a strict vegetarian and that in Pammi-bhabi’s kitchen even eggs were separated from the other foods in the refrigerator. Occasionally chicken or fish had been brought in for from the market for the wedding guests, but there was a special drawer in her kitchen filled with separate eating utensils to ensure that not a molecule of meat or fish contaminated this otherwise strictly vegetarian kitchen.

“Hai hai …. don’t worry. Beejee is the one who suggested it. She just wanted to be sure we keep the cooking pots separately. She said it’s time now since the rest of us do eat non-vegetarian food outside the home. She’s saying she’s modern.” Pammi’s face was alight with a little twinkle in eyes, an expression which would become familiar over the years. Beejee’s new-found interest in “modern” things was definitely going to be exploited by my mischievous and very modern sister-in-law. And often in my name too.

The lovely upstairs bedroom was prepared for me with piles of pillows and a silver tray laden with fruit. Naresh and I had spent our wedding night under an amazing canopy of jasmine which had been lovingly strung and woven together by all five of my bhabis. And for my first visit back to Amritsar, the same huge silver tray laden with fruit was placed by my bed.

Now an hour or so after I arrived, Pammi-bhabi urged me to lie down for a while to rest up for the round of evening visitors and a welcome dinner. I curled up with a lovely golden apple and fell asleep with it still in my hand. When I awoke I could hear the sounds of laughter rising up the stairs and realized the party was in full swing. And it was time to join in.

The following days unrolled in a haze of pleasant moments. Sitting in the mornings in Pammi-bhabi’s beautiful garden with Beejee next to me, pressing my knees and ordering my breakfast to be brought on a tray so she could be sure I was eating properly. Often there was a beautiful apple she’d bought especially for me in the market and kept locked in her cupboard so it would not be purloined before it reached that tray. The cook would produce the apple with a flourish, carefully placing a small knife next to it so I could peel it.

I practiced my Hindi and Beejee insisted on learning English words too. She favored words like “love” and “beautiful” and “clever” so those became the first words we learned in each other’s language. And since the Devanagari or Hindi script is absolutely phonetic, once I learned the extremely refined differences in the “d” and the “t” … both of which had four distinct variants depending on where you placed your tongue … then it was easy to read.

She would hand me the newspaper and I would trace समाचारपत्र letter by letter.

“Samacharpatra ……. newspaper,” I would say. And then slowly pronounce the script on the first page. Not understanding a word, but delighting Beejee who seemed most forgiving of my occasional lapses. A wrong “d” or “t” could produce a very colorful and unsuitable word. Beejee diplomatically ignored my accidental linguistic improprieties.

******

One morning about a week after I arrived, Beejee called me to come downstairs.

“Beday, idahar ao.” I quickly grabbed my dupatta, a long chiffon veil which Punjabi women wore over their tunics and arranged it around my shoulders. Then I bounded down the stairs. Beejee was sitting cross-legged on her bed and I leaned over to touch her feet in the traditional gesture of respect for elders. As I murmured “perapenay” she intercepted my hand and brought it to her lips for a kiss. For twenty years she transformed my willing homage to sheer love with that kiss, quickly seizing my hand before my fingers could touch her toes.

She eased herself off the bed and fumbled among the dozens of keys attached to an ornate silver hook she always wore tucked into the waist of her saree. She selected a key and nodded towards her mandir, a small shrine which many traditional Hindus often have in their bedrooms.

I had only had a brief glimpse of her mandir a few days after my marriage over a year ago. Behind the beautifully carved wooden doors I knew there was a small room filled with brass lamps, pictures of the various Hindu gods and goddesses and a large statue of Lord Krishna in the place of honor. And just inside the doors was a small finely woven silk rug on which Beejee sat for her devotions.

She began her mornings with prayers before this assemblage of gods and goddess, calling them to attention with a few vigorous shakes of a small brass hand bell. For the past week I had woken up to the sound of the bell floating upstairs from her room. And with this delicate but resonating call to prayer came a faint small of sandalwood incense. I would lie in bed for a few extra moments, letting my mind drift in and out of sleep to the accompaniment of Beejee’s bell and the fragrant incense.

Now she fitted the key into the doors and swung them open.

Lord Krishna was still in his prominent place, positioned on his own miniature dais and almost buried under carnation and jasmine garlands. Dozens of smaller statues of other Gods and Goddesses were deployed on a tier of stairs behind him. And the glow of dozens of brass lamps was mirrored and magnified by their polished golden surfaces rendering the whole alcove a blaze of gold.

I recognized Sarasvati, Lakshmi, Hanuman, Ganapati, Parvati … and a backup of several smaller Krishnas. Bright marigolds, the favorite flower for temple offerings, danced amongst the icons and a wonderful array of fruits and sweets was carefully arranged in front of the dazzling tableau.

It was visually gorgeous, replete with all the wonderful symbolism of the Hindu faith. I leaned in to look more closely at the details and my eyes suddenly wandered up to one side of the mandir, There was a photo of Beejee’s late husband with a strand of marigolds across the top of the frame. And something else. Something very familiar.

Placed next to the photo of Naresh’s father was a picture …. of Jesus.

I turned back to Beejee, unable to speak. She whispered softly in Hindi … “I put Him there for you …”

I reached to touch her feet and then bowed my head before Jesus …. and Lord Krishna.

.

.

.

.

* I was married in an Arya Samadhj ceremony, which is often used for mixed marriages. According to some sources, I became a Hindu through marriage. But other sources insist you cannot be converted to Hinduism, you must be born a Hindu. Hindus are uneasy with proselytizing. Still other branches confidently assert that all life is Hindu by default and people are born into other faiths but that it’s all the same in the end. I tend to empathize with the last group.

My total experience of love and acceptance within my Hindu famly solidified the beliefs I held many year earlier as an adolescent. The absence of judgment or prejudice towards whatever faith I had before I married into the Seth family was remarkable. No one ever asked about my religion and no one ever pressured me to adopt any of their cultural traditions. Every small thing I did won immediate appreciation, from wearing the lovely sarees, to learning their handicrafts and joining in the festivals and gleefully thowing colored powders and water around. I loved it all!

For twenty years I experienced unconditional love. And that love became my faith, overwhelming all other beliefs. I am a Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Jew, Taoist and occasional Wiccan. And am gleeful too!

.

What an awesome post! I always find it fascinating reading about how people come to where they are now.

How amazing that you traveled across the world…you must have been so so brave.

When you said that your Dad offered your mum and he to go to India, it brought tears to my eyes. Funny how so often we get terrified of what our parents may say or do, and yet how often their love outshines anything we would have thought them capable of. Fabulous 🙂

I must try Gleeful too 😉

Marilynn

a very interesting story, of your move from one country to another, from one culture to another, and from one religion to another… and you concluded it on a very positive note.

Considering the logjam of cultural and social differences, it is almost inconceivable that you were able to cross the ocean and accept and be accepted into the Hindu society with all its anomalies of caste, race, religion, language and philosophy. That you did straddle the chasm of incongruities is a credit to your tenacity and open mindedness. There are probably dozens of related memories that could be inserted into this general account of your life as an Indian wife.

Hindu society is extremely welcoming , though the complexity of its unity in diversity is very hard for some people to understand and appreciate.

Beautiful story!